Long-distance wood procurement and the Chaco florescence

Author:

Watson

Abstract:

First documented during a military reconnaissance in 1849, Chaco Canyon and the Ancestral Pueblo society that flourished therein [850–1140 Common Era (CE)] have been the focus of archaeological investigation for more than a century. Beginning in the early ninth century CE, the inhabitants of farming communities lining a 14-km stretch of the lower canyon in present-day northwest New Mexico erected massive free-standing masonry pueblos, or “great houses.” Great houses are monumental in scale and are among the most iconic and remarkable feats associated with Chacoan societal development. The construction of one multistory great house, Pueblo Bonito, with at least 650 masonry rooms, required the Chacoan people to quarry 50,000 tons of sandstone and harvest and transport more than 50,000 pine (Pinus sp.), fir (Abies sp.), and spruce (Picea sp.) trees from distant (60−80 km) montane forests (Fig. 1). Guiterman et al.’s (1) analysis of a spatially broad sample of construction timbers from 7 of 11 great houses in Chaco Canyon documents the chronology and spatial extent of wood harvesting strategies and reveals a significant and previously unknown wood source.

Showing posts with label New Mexico. Show all posts

Showing posts with label New Mexico. Show all posts

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

Long-distance Wood Procurement and the Chaco Florescence

Labels:

Anasazi,

ancestral puebloan,

archaeology,

chaco canyon,

New Mexico,

precolumbian

The Implications of the Pollen of the Norian/Rhaetian Triassic New Mexico

Palynology of the upper Chinle Formation in northern New Mexico, U.S.A.: Implications for biostratigraphy and terrestrial ecosystem change during the Late Triassic (Norian–Rhaetian)

Authors:

Lindström et al

Abstract:

A new densely sampled palynological record from the vertebrate-bearing upper Chinle Formation at Ghost Ranch in the Chama Basin of northwestern New Mexico provides insights into the biostratigraphy and terrestrial ecosystem changes during the Late Triassic of northwestern Pangaea. Spore-pollen assemblages from the Poleo Sandstone, Petrified Forest, and 'siltstone' members are dominated by pollen of corystospermous seed ferns (Alisporites) and voltziacean conifers (Enzonalasporites, Patinasporites). Other abundant taxa include Klausipollenites gouldii and the enigmatic fused tetrad Froelichsporites traversei, whereas spores of ferns and fern allies are generally rare. The assemblages are correlated with Zone III Chinle palynofloras of previous authors. The lower assemblages contain rare occurrences of typical Zone II taxa, namely Cycadopites stonei, Equisetosporites chinleanus and Lagenella martini, that may either be reworked or represent relictual floral elements. Marked step-wise losses of species richness, along with only minor appearances of new taxa, led to a total 50% drop in range-through diversity during the late Norian of the Chama Basin. Correlations with other Chinle records in the western U.S. reveal differences in the stratigraphic ranges of some spore-pollen taxa, likely attributable to local/regional differences in environmental conditions, such as groundwater availability, precipitation, nutrients, and temperature, rather than stratigraphic miscorrelation. This is interpreted as a consequence of environmental stress resulting from increased aridity coincident with the northward movement of Pangaea. Similarly, major differences between the western and eastern U.S. and northwest Europe can be attributed to floral provincialism governed by climatic zones during the Late Triassic.

Labels:

New Mexico,

norian,

paleoecology,

paleoenvironment,

palynology,

pollen,

rhaetian,

Triassic

Thursday, December 03, 2015

How Southwestern America's Pueblo's Fell Apart, Physically

The pueblo decomposition model: A method for quantifying architectural rubble to estimate population size

Authors:

Duwe et al

Abstract:

While most archaeological measures of population rely on material proxies uncovered through excavation (rooms, hearths, etc.), we identify a technique to estimate population at unexcavated sites (the majority of the archaeological record). Our case study focuses on ancestral Tewa Pueblo villages in northern New Mexico. Uninhabited aerial vehicle (UAV) and instrument mapping enables us to quantify the volume of adobe architectural rubble and to construct a decomposition model that estimates numbers of rooms and roofed over space. The resulting metric is applied at ten Pueblo villages in the region to ‘rebuild’ architecture, and calculate maximum architectural capacity and the maximum extent of population size. While our focus is on population histories for large Classic period (A.D. 1350–1598) pueblos in the American Southwest, the model and method may be applied to a variety of archaeological contexts worldwide and is not limited to building material, site size, or construction technique.

Labels:

american southwest,

Anasazi,

ancestral puebloan,

archaeology,

New Mexico,

ruins

Sunday, August 02, 2015

Two Bomb Blasts hit Las Cruces, NM Churches Minutes Apart

Two small explosions just 20 minutes and a few miles apart shocked congregants Sunday morning at two churches in southern New Mexico.

There were no injuries from the blasts outside Calvary Baptist Church and Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church in Las Cruces, a police spokesman, Danny Trujillo, said. Each building had minor damage.

Authorities were trying to determine who planted the explosives, what materials were used and whether the blasts were related.

“It doesn’t appear to be coincidental because of the timing, but you never know,” Mr. Trujillo said.

Several agencies, including the F.B.I., the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and the New Mexico State Police, were assisting the investigation.

The first explosive device went off at 8:20 a.m. in a mailbox on a wall near the administrative entrance to Calvary Baptist. The police said several worshipers were inside at the time, but services had not started.

Churchgoers said the explosion shook the building, and there was debris around the damaged mailbox. Sgt. Robert Gutierrez of the Las Cruces Police Department described seeing “just a lot of paper shreds.”

The next blast came from a trash can outside Holy Cross at 8:40 a.m. as Msgr. John Anderson was giving communion.

link.

Labels:

bombs,

church,

las cruces,

New Mexico,

wtf

Tuesday, July 14, 2015

Somehow I Missed This: Tombaugh's Ashes are Aboard New Horizons

When the New Horizons spacecraft flew by Pluto it was the first time mankind has visited what is now called a dwarf planet.

On board that spacecraft, is a man – or rather his ashes – from New Mexico.

Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto as a young astronomer in Arizona. He later moved to New Mexico and founded the astronomy dept at New Mexico State University in 1955.

When NASA launched its Pluto mission 9 years ago, they placed a canister of Tombaugh’s ashes on board the spacecraft.

link.

hm. Perhaps they ought to have named the spacecraft Tombaugh. ah well.

Labels:

astronomy,

dwarf planets,

New Mexico,

NMSU,

planetary science,

pluto,

tombaugh

Wednesday, June 24, 2015

Parrots Push Chaco Canyon (Anasazi/Puebloan) Culture/MesoAmerican Trade Origin Between 800 to 900 AD

Somehow, colorful tropical scarlet macaws from tropical Mesoamerica -- the term anthropologists use to refer to Mexico and parts of northern Central America -- ended up hundreds of miles north in the desert ruins of an ancient civilization in what is now New Mexico.

Early scientists began excavating the large Pueblo settlements in Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico and found the birds' remains in the late 1890s, but only recent radiocarbon dating of the physical evidence has pushed back the time period of sophisticated Pueblo culture by at least 150 years, according to a paper published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Co-author and archaeologist Stephen Plog, the University of Virginia's David A. Harrison Professor of Anthropology, worked with Adam S. Watson of the American Museum of Natural History, Douglas J. Kennett of Pennsylvania State University and a team of researchers from the museum and other universities to have macaw bones dated and interpret the results.

Using accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon methods with high precision in dating, the researchers found the macaw skeletal remains were much older than previously thought -- from as early as the late A.D. 800s -- signaling what researchers theorize was a Pueblo culture established enough to form relationships with Mesoamerican cultures to the south. Plog said archaeologists had typically put the beginning of the apex of ancestral Pueblo civilization in Chaco at A.D. 1040, based on other means such as tree-ring dating that suggested a major architectural expansion began at that time.

Anthropologists had already determined that the ancient Pueblo developed a complex social and religious hierarchy in the canyon, reflected in their distinctive architecture. They have posited that Chaco's 'golden century' or the Chaco 'florescence' occurred from A.D. 1040 to 1110, coinciding with a major expansion of the 'great houses.' These great houses contained clustered complexes of rooms for large gatherings, lodgings, storage, burial and religious rituals. Pueblo Bonito, with about 650 rooms in the largest of the great houses of Chaco Canyon, is where most of the macaws were recovered.

'In general, most researchers have argued that emergence of hierarchy, and of extensive trade networks that extended into Mexico coincided with what we see as other aspects of the Chaco florescence: Roads being built outward from Chaco and the formation of what are called Chaco outliers that mimic the architecture seen in the cultural center,' Plog said.

The radiocarbon dating project, led by Plog, Watson, and Kennett, showed that the bird remains came from as early as the late A.D. 800s to mid 900s. The earlier dating suggests that the rise of Pueblo sociopolitical complexity developed earlier than previously thought.

Labels:

Anasazi,

ancestral puebloan,

chaco canyon,

mesoamerica,

native americans,

New Mexico,

precolumbian,

trade

Monday, June 22, 2015

The Flora of Asselian Permian Equitorial and Seasonally dry Pangea...From Las Cruces, NM

Early Permian (Asselian) vegetation from a seasonally dry coast in western equatorial Pangea: Paleoecology and evolutionary significance

Authors:

Falcon-Lang et al

Abstract:

The Pennsylvanian–Permian transition has been inferred to be a time of significant glaciation in the Southern Hemisphere, the effects of which were manifested throughout the world. In the equatorial regions of Pangea, the response of terrestrial ecosystems was highly variable geographically, reflecting the interactions of polar ice and geographic patterns on atmospheric circulation. In general, however, there was a drying trend throughout most of the western and central equatorial belt. In western Pangea, the climate proved to be considerably more seasonally dry and with much lower mean annual rainfall than in areas in the more central and easterly portions of the supercontinent. Here we describe lower Permian (upper Asselian) fossil plant assemblages from the Community Pit Formation in Prehistoric Trackways National Monument near Las Cruces, south-central New Mexico, U.S.A. The fossils occur in sediments within a 140-m-wide channel that was incised into indurated marine carbonates. The channel filling can be divided into three phases. A basal channel, limestone conglomerate facies contains allochthonous trunks of walchian conifers. A middle channel fill is composed of micritic limestone beds containing a brackish-to-marine fauna with carbon, oxygen and strontium isotopic composition that provide independent support for salinity inferences. The middle limestone also contains a (par)autochthonous adpressed megaflora co-dominated by voltzian conifers and the callipterid Lodevia oxydata. The upper portions of the channel are filled with muddy, gypsiferous limestone that lacks plant fossils. This is the geologically oldest occurrence of voltzian conifers. It also is the westernmost occurrence of L. oxydata, a rare callipterid known only from the Pennsylvanian–Permian transition in Poland, the Appalachian Basin and New Mexico. The presence of in situ fine roots within these channel-fill limestone beds and the taphonomic constraints on the incorporation of aerial plant remains into a lime mudstone indicate that the channel sediments were periodically colonized by plants, which suggests that these species were tolerant of salinity, making these plants one of, if not the earliest unambiguous mangroves.

Labels:

asselian,

las cruces,

New Mexico,

paleobotany,

paleozoic,

pennsylvannian,

Permian

Sunday, April 19, 2015

Los Alamos' Las Conchas Fire Driven by Mountain Waves, Pyro-cumulus clouds

At about 1 p.m. on June 26, 2011, a wind-downed power line sparked a blaze in the Las Conchas area of Santa Fe National Forest. It would become the largest fire in New Mexico’s history at the time. Within hours, the flames spread to cover more than 160 square kilometers, threatening the town of Los Alamos, home of Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), which develops nuclear fuels and safeguards nuclear weapons, among other activities. Now, a new study identifies why the fire spread so far so fast, and the results may have implications for fire management practices in other mountainous regions.

“Between the hours of 8 p.m. and 3 a.m., the Las Conchas Fire exploded from 8,000 acres to 43,000 acres [about 32 to 174 square kilometers],” says Jeremy Sauer, an atmospheric scientist at LANL who participated in the new study, which was presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco in December. To determine how two atmospheric effects — pyro-cumulus clouds and mountain waves — may have contributed to the fire’s overnight blow-up, a team of scientists at LANL, led by Young-Joon Kim, used a computer model that combines atmospheric dynamics with fire physics. Other participating project members included Rodman Linn, Jesse Canfield, Keeley Costigan, and Domingo Muñoz-Esparza, all at LANL.

Pyro-cumulus clouds are towering plumes of water vapor and soot that rise from very large wildfires and that “look very much like large cumulus storm clouds,” Sauer says. By modeling different wind scenarios, they found that the plume created by the Las Conchas Fire may have collapsed in the night due to wind patterns known as mountain waves, which produce gusty surface winds in the evening as air currents cool and descend through mountainous terrain. This would have resulted in “a rapid intensification and spread of the fire,” Kim says.

This scenario also helps explain other anomalous behavior exhibited by the Las Conchas Fire, which increased in intensity overnight and spread rapidly downhill toward Los Alamos. “Typically, fires settle down during the night, and also tend to burn more rapidly uphill, because the flames are reaching upwards,” Sauer says.

link.

Labels:

environment,

fire,

Los Alamos,

New Mexico

Monday, March 30, 2015

Archosauromorph Tanystropheids From Norian Triassic New Mexico

Late Triassic tanystropheids (Reptilia, Archosauromorpha) from northern New Mexico (Petrified Forest Member, Chinle Formation) and the biogeography, functional morphology, and evolution of Tanystropheidae

Authors:

Pritchard et al

Abstract:

We report on tanystropheids from the Late Triassic (middle Norian) Hayden Quarry of northern New Mexico (Chinle Formation, Hayden Quarry). These elements, consisting of isolated vertebrae and appendicular bones, represent the first unambiguously identified tanystropheid from western North America and likely the latest occurrence of the group, postdating Tanytrachelos in the eastern United States. A new phylogenetic analysis of early saurians identifies synapomorphies of tanystropheid subclades, which are recognized in the recovered vertebrae and a calcaneum. The femora are consistent with referral to Tanystropheidae. There is no clear association of the remains, however, so we refrain from erecting a new taxon. The analysis also indicates that the Hayden Quarry tanystropheid fossils belong to a newly recognized clade including the Late Triassic taxa Langobardisaurus and Tanytrachelos. Because most tanystropheid specimens are two-dimensionally crushed skeletons, the Hayden Quarry tanystropheid fossils provide valuable insights into the three-dimensional osteology of derived tanystropheids. The most striking feature of the Hayden vertebrae is a rugose, flattened expansion of the neural spines in the dorsal, sacral, and caudal regions, probably linked to a ligamentous bracing system. These fossils and others from Late Triassic sites in the American West suggest that tanystropheids underwent a previously unrecognized radiation in North America just prior to their extinction.

Labels:

archosauromorpha,

fossils,

New Mexico,

norian,

paleontology,

Tanystropheids,

Triassic

Tuesday, March 24, 2015

The Composition and Layout of a Wolfcampian/Lower Permian Woodland

Plant architecture and spatial structure of an early Permian woodland buried by flood waters, Sangre de Cristo Formation, New Mexico

Authors:

Rinehart et al

Abstract:

Natural molds of 165 stems were found in life position in a 1 m-thick sandstone bed, lower Permian (Wolfcampian), Sangre de Cristo Formation, northern New Mexico. The sandstone represents a single flood event of a river sourced in the Ancestral Rocky Mountains. Most of the flood-buried plants survived and resumed growth. The stem affinities are uncertain, but they resemble coniferophytic gymnosperms, possibly dicranophylls. Stem diameters (N = 135) vary from 1 to 21 cm, with three strongly overlapping size classes. Modern forest studies predict a monotonically decreasing number (inverse square law) of individuals per size class as diameter increases. This is not seen for fossil stems ≤ 6 cm diameter, reflecting biases against preservation, exposure, and observation of smaller individuals. Stems ≥ 6 cm diameter obey the predicted inverse square law of diameter distribution. Height estimates calculated from diameter-to-height relationships of modern gymnosperms yielded heights varying from ~ 0.9 m to greater than 8 m, mean of ~ 3 m. Mean stand density is approximately 2 stems/m2 (20,000 stems/hectare) for all stems greater than 1 cm diameter. For stems greatre than than 7.5 cm or greater than 10 cm diameter, density is approximately 0.24 stems/m2 (2400 stems/hectare) and 0.14 stems/m2 (1400 stems/hectare). Stem spatial distribution is random (Poisson). Mean all-stem nearest-neighbor distance (NND) averages 36 cm. Mean NND between stems greater than 7.5 cm and greater than than 10 cm diameter is approximately 1.02 m and 1.36 m. NND increases in approximate isometry with stem diameter, indicating conformation to the same spatial packing rules found in extant forests and other fossil forests of varying ages. Nearest-neighbor distance distribution passes statistical testing for normality, but with positive skew, as often seen in extant NND distributions. The size-frequency distribution of the stems is similar to those of Jurassic, early Tertiary, and extant woodlands; the early Permian woodland distribution line has the same slope, but differs in that the overall size range increases over time (Cope's rule). The early Permian woodland is self-thinning; its volume versus density relationship shows a self-thinning exponent between − 1.25 and − 1.5, within the range seen in some extant plant stands (− 1.21 to − 1.7).

Labels:

Artinskian,

asselian,

lower permian,

New Mexico,

paleobotany,

paleoecology,

Permian,

Sakmarian,

wolfcampian

Thursday, January 15, 2015

Maize had a Complex Path Into the American Southwest

After it was first domesticated from the wild teosinte grass in southern Mexico, maize, or corn, took both a high road and a coastal low road as it moved into what is now the U.S. Southwest, reports an international research team that includes a UC Davis plant scientist and maize expert.

The study, based on DNA analysis of corn cobs dating back over 4,000 years, provides the most comprehensive tracking to date of the origin and evolution of maize in the Southwest and settles a long debate over whether maize moved via an upland or coastal route into the U.S.

Study findings, which also show how climatic and cultural impacts influenced the genetic makeup of maize, will be reported Jan. 8 in the journal Nature Plants.

The study compared DNA from archaeological samples from the U.S. Southwest to that from traditional maize varieties in Mexico, looking for genetic similarities that would reveal its geographic origin.

"When considered together, the results suggest that the maize of the U.S. Southwest had a complex origin, first entering the U.S. via a highland route about 4,100 years ago and later via a lowland coastal route about 2,000 years ago," said Jeffrey Ross-Ibarra, an associate professor in the Department of Plant Sciences.

The study further provided clues to how and when maize adapted to a number of novel pressures, ranging from the extreme aridity of the Southwest climate to different dietary preferences of the local people.

Excavations of multiple stratigraphic layers of Tularosa cave in New Mexico allowed researchers to compare genetic data from samples from different time periods.

link.

Labels:

agriculture,

american southwest,

corn,

maize,

mesoamerica,

native americans,

New Mexico,

North america,

precolumbian

Monday, October 13, 2014

Earth Observing Satellites Note Large Methane Leaks From American SouthWest/Four Corners Regions

An unexpectedly high amount of the climate-changing gas methane, the main component of natural gas, is escaping from the Four Corners region in the U.S. Southwest, according to a new study by the University of Michigan and NASA.

The researchers mapped satellite data to uncover the nation's largest methane signal seen from space. They measured levels of the gas emitted from all sources, and found more than half a teragram per year coming from the area where Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah meet. That's about as much methane as the entire coal, oil, and gas industries of the United Kingdom give off each year.

Four Corners sits on North America's most productive coalbed methane basin. Coalbed methane is a variety of the gas that's stuck to the surface of coal. It is dangerous to miners (not to mention canaries), but in recent decades, it's been tapped as a resource.

"There's so much coalbed methane in the Four Corners area, it doesn't need to be that crazy of a leak rate to produce the emissions that we see. A lot of the infrastructure is likely contributing," said Eric Kort, assistant professor of atmospheric, oceanic and space sciences at the U-M College of Engineering.

link.

Labels:

american southwest,

arizona,

Colorado,

four corners,

methane,

New Mexico,

Utah

Tuesday, September 16, 2014

?!?!?!?!?!!!!!

Labels:

cities,

Los Alamos,

New Mexico,

USA,

wealth

Thursday, August 28, 2014

Edestus: The Weirdest Shark EVER?!

Edestus, the Strangest Shark? First Report from New Mexico, North American Paleobiogeography, and a New Hypothesis on its Method of Predation more

Author:

Itano

Abstract:

Two incomplete teeth of the chondrichthyan genus Edestus are reported. They were collected fromthe Gray Mesa Formation (Pennsylvanian, late Desmoinesian), Socorro County, New Mexico, in 1996.The better-preserved tooth belongs to Edestus sp. cf. E. heinrichi. The other cannot be identifiedbeyond the generic level. These are the first specimens of the genus known to be reported from NewMexico. The only other specimens known from the Rocky Mountain region are from Colorado. Boththe New Mexico and Colorado collections are from marine limestones. In North America, Edestus ismost common in marine black shales of the Illinois Basin, but to date has not been found in marinegray shales or limestones in the Appalachian Basin. The failure to find Edestus remains in the Appalachian Basin is probably the result of the precise timing and limited extent of marine incursionsinto that region. Edestus might have been less tolerant of restricted marine environments than otherchondrichthyans collected from Pennsylvanian deposits in the Appalachian Basin. The function of thesymphyseal tooth whorls of Edestus is obscure, inasmuch as their convex curvature makes them poorly-adapted to the “scissors” function proposed in some previous studies. Alternatively, it is pro-posed here that Edestus teeth were used to disable prey with a slicing action carried out with a verticalmotion of the head, with jaws fixed relative to each other, and not with a scissors-like action of thejaws moving relative to each other. This hypothesis is supported by the author’s observations of wearand damage on the teeth of the holotype of Edestus newtoni. Helicoprion tooth whorls are similar to those of Edestus in that they contain sharp, serrated tooth crowns along the convex margin of the whorls and extend outside the oral cavity. The whorls might have functioned similarly to the mannerthat is hypothesized for Edestus,that is, to slash prey with a downward motion of the head, with jawsfixed. This proposed similarity in form and function would likely represent convergence

.

Labels:

carboniferous,

fish,

fossils,

mississippian,

moscovian,

New Mexico,

paleobiology,

paleontology,

sharks

Thursday, August 07, 2014

Bucking Mainstream Thought: Chaco Canyon NOT Abandoned for Environmental Reasons

Prehistoric deforestation at Chaco Canyon?

Authors:

Wills et al

Abstract:

Ancient societies are often used to illustrate the potential problems stemming from unsustainable land-use practices because the past seems rife with examples of sociopolitical “collapse” associated with the exhaustion of finite resources. Just as frequently, and typically in response to such presentations, archaeologists and other specialists caution against seeking simple cause-and effect-relationships in the complex data that comprise the archaeological record. In this study we examine the famous case of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, during the Bonito Phase (ca. AD 860–1140), which has become a prominent popular illustration of ecological and social catastrophe attributed to deforestation. We conclude that there is no substantive evidence for deforestation at Chaco and no obvious indications that the depopulation of the canyon in the 13th century was caused by any specific cultural practices or natural events. Clearly there was a reason why these farming people eventually moved elsewhere, but the archaeological record has not yet produced compelling empirical evidence for what that reason might have been. Until such evidence appears, the legacy of Ancestral Pueblo society in Chaco should not be used as a cautionary story about socioeconomic failures in the modern world.

Labels:

Anasazi,

ancestral puebloan,

archaeology,

chaco canyon,

New Mexico,

precolumbian,

unm

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Wednesday, July 16, 2014

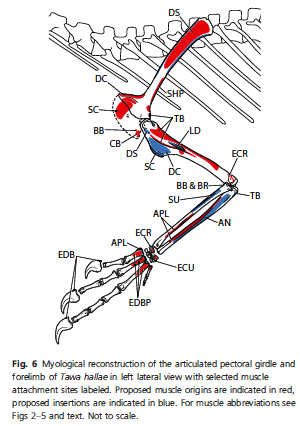

The Arms of Tawa hallae, a Theropod Dinosaur From Norian Triassic New Mexico

Complete forelimb myology of the basal theropod dinosaur Tawa hallae based on a novel robust muscle reconstruction method

Author:

Burch

Abstract:

The forelimbs of nonavian theropod dinosaurs have been the subject of considerable study and speculation due to their varied morphology and role in the evolution of flight. Although many studies on the functional morphology of a limb require an understanding of its musculature, comparatively little is known about the forelimb myology of theropods and other bipedal dinosaurs. Previous phylogenetically based myological reconstructions have been limited to the shoulder, restricting their utility in analyses of whole-limb function. The antebrachial and manual musculature in particular have remained largely unstudied due to uncertain muscular homologies in archosaurs. Through analysis of the musculature of extant taxa in a robust statistical framework, this study presents new hypotheses of homology for the distal limb musculature of archosaurs and provides the first complete reconstruction of dinosaurian forelimb musculature, including the antebrachial and intrinsic manual muscles. Data on the forelimb myology of a broad sample of extant birds, crocodylians, lizards, and turtles were analyzed using maximum likelihood ancestral state reconstruction and examined together with the osteology of the early theropod Tawa hallae from the Late Triassic of New Mexico to formulate a complete plesiomorphic myology for the theropod forelimb. Comparisons with previous reconstructions show that the shoulder musculature of basal theropods is more similar to that of basal ornithischians and sauropodomorphs than to that of dromaeosaurids. Greater development of the supracoracoideus and deltoideus musculature in theropods over other bipedal dinosaurs correlates with stronger movements of the forelimb at the shoulder and an emphasis on apprehension of relatively large prey. This emphasis is further supported by the morphology of the antebrachium and the intrinsic manual musculature, which exhibit a high degree of excursion and a robust morphology well-suited for powerful digital flexion. The forelimb myology of Tawa established here helps infer the ancestral conformation of the forelimb musculature and the osteological correlates of major muscle groups in early theropods. These data are critical for investigations addressing questions relating to the evolution of specialized forelimb function across Theropoda.

Labels:

dinosaurs,

fossils,

New Mexico,

nonavian dinosaurs,

norian,

paleontology,

theropods,

Triassic

Tuesday, May 27, 2014

A Little bit of Awesomeness: the Ties Between the USS New Mexico & Mesilla's La Posta Restaurant

On a weekday afternoon Dick Brown, Chairman of the USS New Mexico committee of the Navy League is giving a presentation about the nuclear-powered submarine to an audience at the Branigan Cultural Center in Las Cruces.

Brown gives these updates to people all over the state to raise awareness and funds for the crew of the USS New Mexico.

“We do things for the crew that the Navy cannot do. One of those things is that we bring crew members to New Mexico so that they understand the state a little bit better. They learn about the geography, the history, and the culture. We usually have about five or six sailors about twice a year,” says Brown.

According to Brown, the crew has learned much about New Mexico and the submarine also has a southwest decor throughout the ship that is hard to miss.

“There are pictures of Carlsbad Caverns, The Balloon Fiesta, and White Sands. The bunk curtains have a Southwest-Native American design, including the pilot, and co-pilot chairs in the diving station,” says Brown.

Another part of the USS New Mexico that shares something in common with the state is the galley, or kitchen. It is named after La Posta de Mesilla, a popular Southern New Mexico restaurant housed in a centuries-old adobe building in the town of Mesilla.

Navy Captain Mark Prokopius, a former commander of the USS New Mexico shares the story about a contest that led to the naming of the submarine’s galley.

“When we decided that we were going to name our galley we put it up to the crew and there were several restaurants that were in the running to be named,” says Cpt. Prokopius.

Tom Hutchinson owns and operates La Posta de Mesilla with his wife Jerean. He is a former Navy Captain and aviator and actually worked with submarines during his time in the Navy.

“They sent several of their Mess specialists down here and trained with us for two to three days, took all that information after visiting all of the establishments back to Virginia, visited with the Skipper and the final vote and tally was that they would name their galley after La Posta de Mesilla,” says Hutchinson.

The crew decided to name it La Posta Abajo del Mar (La Posta under the sea). Captain Prokopius says that restaurant in Mesilla really represented what the crew was looking for.

“When I sold this to the crew and told them about La Posta being a family-owned, Tom Hutchinson being a former Navy captain, and a family oriented restaurant; It really seemed like a perfect fit,” says Cpt. Prokopius.

After the contest ended the crew's culinary specialists were sent to the restaurant to learn recipes. Hutchinson and his employees gave the crew members a firm understanding of the restaurant’s cuisine.

link.

Labels:

green chile,

mesilla,

New Mexico,

restaurants,

submarines,

TEH AWESOME,

us navy,

USN

Monday, May 26, 2014

Using Drones to Thermally map a Chaco-era Anasazi/Ancestral Puebloan Site

Archaeological aerial thermography: a case study at the Chaco-era Blue J community, New Mexico

Authors:

Casana et al

Abstract:

Despite a long history of studies that demonstrate the potential of aerial thermography to reveal surface and subsurface cultural features, technological and cost barriers have prevented the widespread application of thermal imaging in archaeology. This paper presents a method for collection of high-resolution thermal imagery using an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), as well as a means to efficiently process and orthorectify imagery using photogrammetric software. To test the method, aerial surveys were conducted at the Chaco-period Blue J community in northwestern New Mexico. Results enable the size and organization of most habitation sites to be readily mapped, and also reveal previously undocumented architectural features. Our easily replicable methodology produces data that rivals traditional archaeological geophysics in terms of feature visibility, but which can be collected very rapidly, over large areas, with minimal cost and processing requirements.

Labels:

Anasazi,

ancestral puebloan,

archaeology,

chaco canyon,

New Mexico

Friday, April 18, 2014

The Diversity of Small Theropod Dinosaurs From the Santonian to Maastrichtian Cretaceous in New Mexico

Small Theropod Teeth from the Late Cretaceous of the San Juan Basin, Northwestern New Mexico and Their Implications for Understanding Latest Cretaceous Dinosaur Evolution

Authors:

Williamson et al

Abstract:

Studying the evolution and biogeographic distribution of dinosaurs during the latest Cretaceous is critical for better understanding the end-Cretaceous extinction event that killed off all non-avian dinosaurs. Western North America contains among the best records of Late Cretaceous terrestrial vertebrates in the world, but is biased against small-bodied dinosaurs. Isolated teeth are the primary evidence for understanding the diversity and evolution of small-bodied theropod dinosaurs during the Late Cretaceous, but few such specimens have been well documented from outside of the northern Rockies, making it difficult to assess Late Cretaceous dinosaur diversity and biogeographic patterns. We describe small theropod teeth from the San Juan Basin of northwestern New Mexico. These specimens were collected from strata spanning Santonian – Maastrichtian. We grouped isolated theropod teeth into several morphotypes, which we assigned to higher-level theropod clades based on possession of phylogenetic synapomorphies. We then used principal components analysis and discriminant function analyses to gauge whether the San Juan Basin teeth overlap with, or are quantitatively distinct from, similar tooth morphotypes from other geographic areas. The San Juan Basin contains a diverse record of small theropods. Late Campanian assemblages differ from approximately co-eval assemblages of the northern Rockies in being less diverse with only rare representatives of troodontids and a Dromaeosaurus-like taxon. We also provide evidence that erect and recurved morphs of a Richardoestesia-like taxon represent a single heterodont species. A late Maastrichtian assemblage is dominated by a distinct troodontid. The differences between northern and southern faunas based on isolated theropod teeth provide evidence for provinciality in the late Campanian and the late Maastrichtian of North America. However, there is no indication that major components of small-bodied theropod diversity were lost during the Maastrichtian in New Mexico. The same pattern seen in northern faunas, which may provide evidence for an abrupt dinosaur extinction.

Labels:

campanian,

cretaceous,

dinosaurs,

fossils,

maastrichtian,

mesozoic,

New Mexico,

nonavian dinosaurs,

paleontology,

santonian,

teeth,

theropods

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)